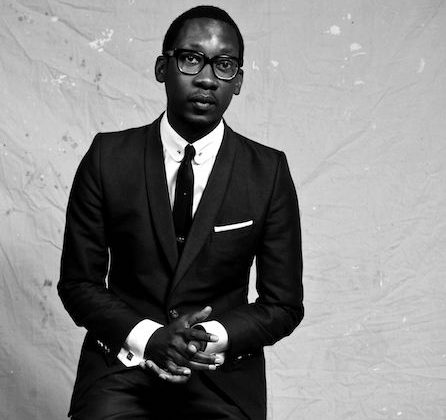

Kalaf Epalanga is an Angolan musician, writer, and journalist best known as a member of the popular music group Buraka Som Sistema. Buraka Som Sistema, which was founded in Lisbon, introduced Kuduro –a fusion of techno and Angolan dance music- to a worldwide audience. As Kalaf notes, what has made Kuduro so appealing and Buraka Som Sistema so famous has been their commitment to safeguarding the joyful sound of “a genre of music created by disenfranchised kids in Angola.” Through this music, Kalaf has become a cultural ambassador showcasing the beauty and depth of Angolan creative expressions. With this success, Kalaf has tried to shine a light on issues of migration, especially the economic and cultural contribution of Africans living in Europe.

In this interview, which was recorded April 6, 2019, at the African Book Festival in Berlin, Kalaf discusses the theme of the conference, Transitioning From Migration. Our conversation touches on the Lusophone experience, where we look at migration through the scope of Angolan identity, language, and music. Kalaf’s commentary is acute and enlightening; especially the way he dissects the historical, economical, and cultural factors driving migration. What stands out about this conversation is his belief in storytelling; whether that is done through music or books, like his newest one Whites Can Dance Too. In this story, Kalaf shares his narrative to demystify the process of migration and how music has allowed him to cross many borders and unite diverse audiences. It is through the belief that music can be a transformative agent – a tool for storytelling and uniting people – where we begin to engage the concept of transitioning from migration. In this sense we begin to see that self-expression and individual stories have the power to create a collective portrait of African life and kinship.

Lydia: Kalaf, what does your name mean?

Kalaf: My name is Muslim. It means the heir, successor.

Lydia: How do you feel about your name? Or put another way, how do you engage your name?

Kalaf: My name Epalanga is an Angolan name. It’s from the Umbundu Kingdom. For my people, Epalanga is a title we give to a person in charge in the absence of the King or Soba the leader of a village. In our tradition, we don’t have surnames. So groups that had contact with Portuguese adopt surnames, but it’s not common. My father has a European surname, same with my uncle and grandparents. We’re Ovimbundu, a Bantu ethnic group and the tradition of having surnames came with Europeans. A lot of people adopt Epalanga as a surname. It’s common to find a lot of Epalangas where I’m from but not all of them are related.

Lydia: What about your children, do they have the same surname?

Kalaf: My kids, I gave them an Angolan name and put Epalanga next to it. I have a history with it. I inherited it from my grandfather. Epalanga is very important for me because it’s very obvious I come from those people. You cannot find that name anywhere else even though there are eighteen tribes in Angola. It’s a very specific title for Umbundu people.

Lydia: Why is it important to make sure your kids have that specific identity?

Kalaf: Because they are born in Europe. They are of mixed race, so for me giving them Angolan names somehow is giving them a map so they can trace and search for more information. Even though I believe in teaching history, I also don’t like to force history on people. I give them tools or tips for them to research for themselves, starting with their names. These are my choices and my wife’s, even though she’s European.

Lydia: You know this conference is titled Transitioning from Migration, and we’re Africans living in the diaspora, how would you take that theme analyze it, assess it, and say: it makes sense to me in this context?

Kalaf: It’s very complex. What I like and what I somehow indulge in my work is always to make sure I’m introduced as an immigrant. I always find the contributions of immigrants very important for the local culture they are engaged with or moved into. Not just economically, for obvious reasons most come to do the dirty work- but also when it comes to showing the consequences of the other migration, what the European did when they went to Africa. I always find it important to reverse the tables and also put mirrors in front of people. I make the effort of making sure our hosts do not forget why we’re here; it’s a consequence of something larger than us. It’s all part of the same history, the same dark, and sad history. So for me, although I struggle with the idea- when is the right time to go back to my country— I always find reasons to stay because my work has opened certain doors and put me in certain rooms where most of the time I’m the only black person. I use my presence as a mirror and even use the word expat when I start my talk. Hello, my name is Kalaf Epelanga I’m an expat. By using language by using these words, I’m able to put a mirror in front of people. That’s how I access and process transitioning from migration.

Lydia: What you’re saying is phenomenal in terms of how we use words to empower and also to strip away people’s power. In Europe now, people who come on boats from Africa are referred to as migrants, not expats. And that word “migrant” has a negative connotation.

Kalaf: I call them expats because most of them come to work.

Lydia: …and to enrich the language culture, food, and market culture.

Kalaf: It’s a fair trade. It doesn’t start from a good starting point because most of them face the harsh reality of European policies. But I sympathize with that group of people because I am a newer European. I only got my Portuguese citizenship four years now. Even in my professional life, I encountered a lot of issues. I know all the embassies; I know everything. I studied immigration laws, I read about it. Even the reason I got my citizenship [was that] I read that they only give it to you if you are six years in the country, paying taxes, and six years with your residency card. You have to have that card renewed three times and then can apply.

But I didn’t have six years, because I came as a student, stayed out of status for a period of time, and then I began that process of getting it. I was a drop out; I couldn’t renew my student visa. I had to find a job that could give me a visa so I could get my residency card. The only way to jump that [requirement] was to create my own company, which in the end was good because I created my record label. That is how I became an independent record producer. Otherwise, I would have signed to another label and lived my life but the fact [was] I needed a job, so I created my own job.

Then I was reading that Portugal allows very special citizens to get citizenship, it’s a law that allowed Brazilian players to get citizenship to play for the national team. I call my lawyers and say, “there is this law here. If I prove that I’m as important as a football player, then I can get my citizenship.” And that was the process. I had a pile of documents to prove I was relevant. And I tell that story because there are people that I know, who are incredible artists doing great jobs and are in that situation. In Portugal, don’t hide your story; it can be useful for some people.

Lydia: You’re very open about discussing your immigration struggles, but what about that artist who has to hide because he fears the scrutiny brought to someone who is not yet stabilized?

Kalaf: The main problem – even among us Africans- is we don’t talk to each other. We don’t share our stories. There are Africans like me, with their European citizenship, who don’t care about politics, who don’t vote. And I know for a fact, me not exercising that privilege messes up the lives of a lot of people like me. It’s very important that for us that have it we cannot play around. We can’t just say now I have a passport. I’m going to be quiet. I understand that before you had to be quiet because you were a guest but now that you’re part of it, you need to use it.

I learned this from one of my mentors. A tiny black man that every time he had an interaction with the police– he’d take his Portuguese ID card and raise it in the air. Just to say, you cannot touch me. With that attitude, I knew that that document is a privilege. And you cannot be silent. If you have it, you have to be louder. That’s how I see it. Shout as loud as you can.

Lydia: When you left Angola, what were your expectations of Portugal?

Kalaf: Get a degree and move out as soon as possible.

Lydia: How come?

Kalaf: Because I love my country. It took me two years to unpack my bags.

Lydia: Tell me about Angola. What is the Angolan Experience—what do you love about Angola that shapes your character?

Kalaf: There are few of us. We cannot waste our knowledge; we cannot waste our minds. The country was at war for thirty plus years. So we all feel this need to give our contribution. It’s an unspoken rule. Even when I decided to stay in Europe, the artists I produce are artists from Angola. I always send them tickets. Show them the way and say this is how you can do it. Most of them don’t want to leave Angola. They make way more money there than in Europe. I totally get it, but having an open mind and interactions with other Africans is important. That is something we [have] suffered with because we were the last country to be independent, 1975. We don’t have interaction with our neighbors. Not only because of the consequences of colonialism but also the cold war, which was more perverse. We often don’t acknowledge how cold war destroyed our fragile independence.

We were facing neocolonialism in certain aspects, and we were facing consequences of the cold war. We had the African Vietnam in our country. I saw a generation of my elder cousins being killed.

So when it comes to my country, I cannot erase that sense of duty. Not even by distance. Then I start having all these anxieties. Oh! I live in Europe. I am helping this place become richer, not just economically but also culturally. I’m contributing to this place so in my head, I think, I need to go back. But as I evolve, now I understand that I can bridge the gap. Lead by example. I can go to a twenty-year-old aspiring writer or musician and say, these were my mistakes. Go to South Africa; learn English. Know your neighbors. These were my mistakes. I’m ashamed I know so little about neighboring countries. And now information that comes around about Uganda or Zimbabwe, I absorb because I got to.

And now, also, flights are getting cheaper. It’s better to travel from Angola to South Africa. Take advantage of that. More importantly, let’s force our politicians to suppress paperwork in our embassies that make it difficult to travel between our countries. We need to push that.

Lydia: Thank you for that insight. Since we are at a book festival—let’s discuss your books:

Kalaf— My first two books are collections of flash fiction. The first one, [is titled] Love Stories For Colored Kids. The second is The Angolan Who Bought Lisbon At Half The Price. This story was inspired by a group of Angolans coming to Portugal and buying up companies in distress. On a personal story—I was being confused for one of these Angolans. One day in a very tiny restaurant I was having lunch, the owner came out and asked me: Are you Angolan? I said, yes. He looked at me apprehensively; I’m selling my restaurant, do you want to buy it? What’s the condition? So he took me to the kitchen, showed me the place, and I don’t have money to buy the restaurant, but the man was so desperate he didn’t even see me as a regular client. An Angolan in a suit must have money; let me pitch. I write about this relationship between Angola and Portugal.

My latest book is a novel: Whites Can Dance Too—came out in Portugal 2017 and Brazil 2018. It’s about music and dance; one of my mentors José Eduardo Agualusa, invited me to talk about Kuduro in a music and literature festival in Rio de Janeiro. My band is known for bringing Kuduro to the world. He invited me to talk about Kuduro, and I was talking to a Brazilian audience about how every time I went to perform the audience would be upper-middle-class whites. This was the first time I was talking to a black audience in Brazil because the festival catered to that group, and I found it absurd because we know so little about each other. At the end of the talk, Jose said—you must write a biography of Kuduro, this music genre that was created by poor, disenfranchised kids in Angola. That idea stuck with me and I decided to write that story using my own experiences.

Lydia: Lastly, who are some of your favorite authors?

Kalaf: Hilda Hilst, Toni Morrison, José Luandino Viera, James Baldwin and João Ubaldi Ribeiro!

Kalaf Epalanga will be participating in the Africa Writes Festival taking place July 5-7, 2019 at the British Library in London. His music group, Buraka Som Sistema, which fuses Kuduro with techno, can be found on ITunes. Also, his books: Love Stories for Colored Kids, The Angolan Who Bought Lisbon At Half The Price, and Whites Can Dance Too are available online.

Image by Matthew Pandolfe with permission by Kalaf Epalanga

Lydia Kakwera Levy