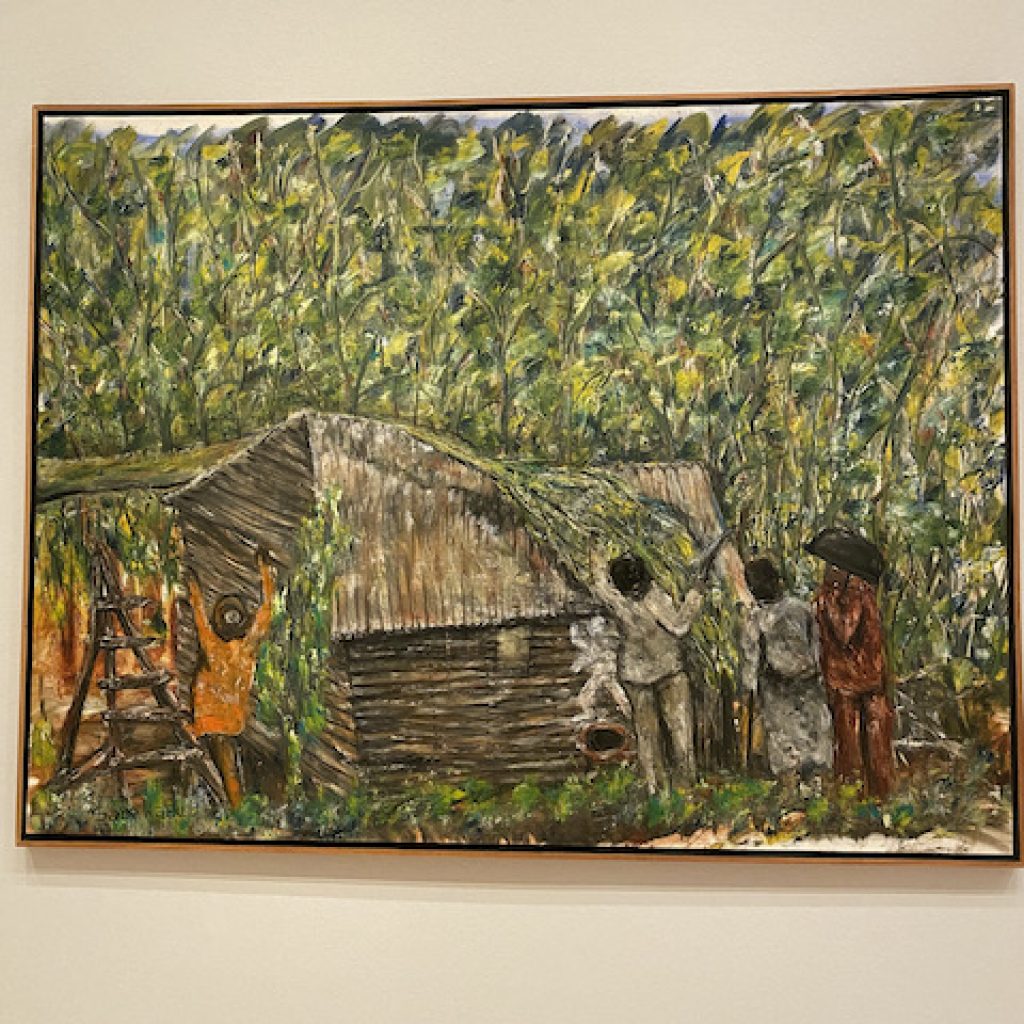

Original and electrifying—Michael Armitage’s exhibition, Paradise Edict, which is showing at the Royal Academy of Arts, covers themes of history, continuity and cultural preservation. Born and raised in Kenya, Armitage is best known for his exceptional large oil paintings produced on Lubugo cloth, a ceremonial bark material harvested from the Mutuba tree. The Mutuba tree is an indigenous tree found in Central and Western Uganda whose production follows a delicate process that strips out inner layers of material without damaging the rest of the tree. Armitage uses this cloth–with its holes and imperfections—to illustrate the continuity between indigenous artistic traditions and contemporary art production. In many ways, his originality shines through; his paintings are large in scale; they incorporate rich, vibrant colors; and they are overflowing with texture and humor. As one admirer of his work pointed out, “Michael’s paintings are alive. They have movement—there is movement within the work. And I love that.”

One thing that stands out about the exhibition is its title, Paradise Edict. This phrase was inspired by the contradictory nature of election rhetoric during the contested 2017 Kenyan election. Armitage examined how opposing groups offered up Utopic ideas of leading people to the promised land; speeches that were cast against the backdrop of violence. In his paintings, we see both the celebratory aspects of politics and its volatile nature. As one fan told me, “The best artists don’t tell you the story—you look at the art, and you feel the story, and you think about it. You wonder about the situation and the context; they don’t push their perspective/opinion of the situation.” This observation is well executed as you see characters in lush green environments, some being pushed and pulled, some with sling shots, and others maintaining a confident swagger unbothered by the chaos around them. This attention to detail is evident in the above featured painting, The Chicken Thief. In this work, Armitage gives us a protagonist that sees opportunity in the chaos and is able to confidently take what he wants.

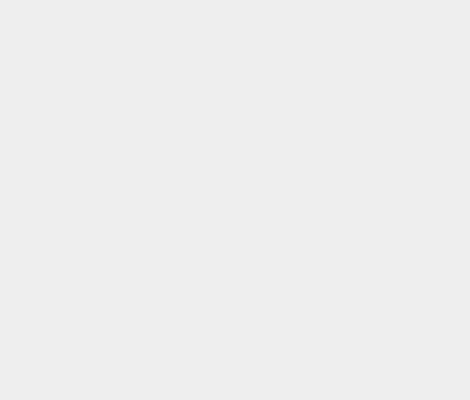

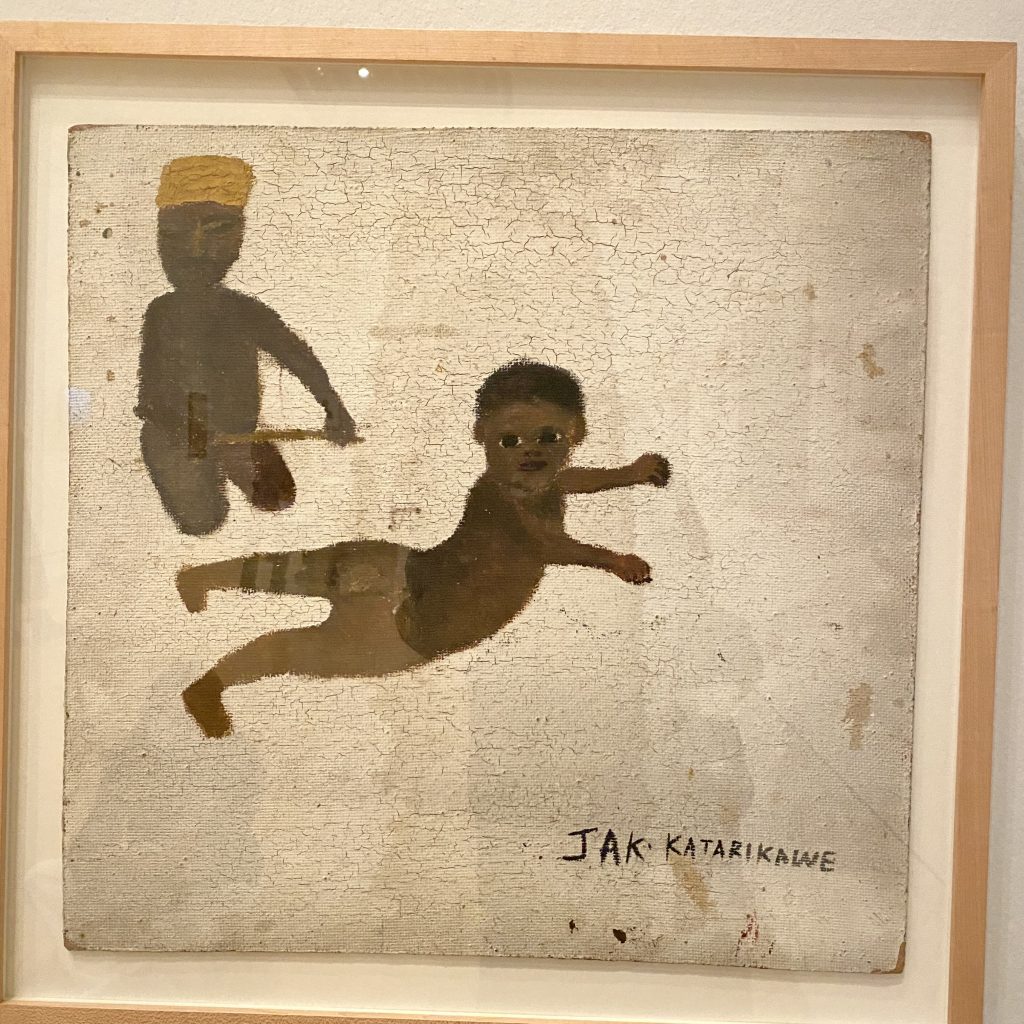

Beyond the material, Armitage’s journey is also guided by other East African artists. That is why it is such a treat to see the inclusion of old masters like Jak Katarikawe, Theresa Musoke, Meek Gichugu, Asaph Ng’ethe Macau, Elimo Njau, and Sane Wadu.Having this group showing is very special because right now—when you attend contemporary art shows—we see many opportunities for younger artists from Africa; we see that those born 1980 and beyond are commanding tremendous attention on the global art scene which should be applauded. This show broadens that view of contemporary art on the African continent by showing us that historiography.

The group show provides great context for understanding the genesis of contemporary art practices in East Africa, the influence of the Margaret Trowell’s School of Fine Art, and the impact these old masters have had on emerging artists. We see artists who have been working for a very long time but for many reasons were denied global recognition finally have their moment. Now, the audience can listen to their stories through the videos; we hear directly about how the art survived despite political instability and economic hardships. As a friend of mine noted, this exhibition is about “The culture and their story surviving through their art.”

Overall, Armitage has helped us to see the importance of art production to cultural and material preservation. These artists have recorded the history of east Africa; they have explored themes that touch on history, politics, comunity and the family. Essentially, the artist has become the historian.They should be celebrated.

Note: Michael Armitage, Paradise Edict, showing at The Royal Academy of Art, 22 May-19 September 2021.

Review by Lydia Kakwera Levy