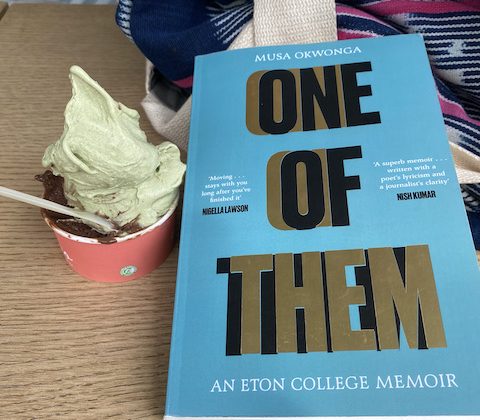

Most of us have heard of Eton College, a school that casts a formidable shadow in Britain’s elite society. It is a school that has educated a long line of prime ministers, royals, and other wealthy individuals. When you consider Eton’s place in the world, a tiny number of people can claim to have attended the school—and that number dwindles when you count black working class students. Because access is often determined by money and clout, family history, and top academic scores—not many people even meet the threshold for applications. That is why Musa Okwonga’s memoir, One of Them, is so compelling. It is a behind-the-scenes look at this exclusive institution told from a black student’s perspective. In his powerful and timely memoir, Okwonga reflects on the intersectionality of elite education, privilege, and race. He shows us the promises and pitfalls of elite private school education.

After watching a documentary about Eton, Okwonga convinces his mother to send him there. He believes that Eton “is the best school in the world, the home of past and future heads of state, and if I succeed there, I can succeed anywhere.” In his imagination [and many people’s for that matter], Eton is a pathway to success. When Okwonga arrives at Eton, he is aware that his background differs significantly from his peers. He is a gifted young black student from an immigrant and working class community. Most of his classmates are white, affluent, and members of the aristocracy. Even with his powerhouse academic abilities, Okwonga never quite feels settled at Eton. Racism and microaggression keep popping up to put him in his place. So Okwonga tries to blend in; he tries to “avoid detection,” a term that can best be defined as trying to be invisible. This invisibility serves as armor to protect him from the negative stereotypes often heaped on black people.

At Eton, Okwonga chooses to throw his energy into attaining “academic excellence.” In many ways, Eton delivers on what it promises. The school provides students with pristine campus facilities, majestic halls, and grounds. They have top-notch professors, exam preparation resources, and access to top universities. At an age of self-discovery, students at Eton get a taste of their own power. They dress in formal attire, they speak with posh accents—the psychological impact is to embrace privilege. It is not surprising that many of the alumni go on to occupy prominent positions in business, law, and government. Yet, one would think that this level of success would encourage empathy for the plight of working class citizens. It doesn’t. Okwonga argues that “political leaders from Eton have driven through some of the most regressive policies in recent memory.” In his assessment—this political callousness partly comes from the school’s competitive environment, where young people are taught to “win at all costs.” More problematic is the view that success comes from personal effort and failure is a “self-inflicted” wound. In essence, the main pitfalls of such an exclusive education is indifference toward poverty.

This observation is in line with a growing wave of commentary that says private schools widen the inequality gap. Many critics argue that private schools are fortresses of advantage, smoothing out bumps for the elite. As a friend of mine noted, “Okwonga is spot on. Private education is the starting foundation of inequality. It is how we are segregating the entire society and giving people advantages; everything that a child needs is provided to them. In this exclusive environment, many students can see their trajectory, because their life is mapped out for them.”Another parent summed it up this way: “If you go to Eton, you’ll find that many children are well behaved, well mannered, and hardworking because they struggled for that placement. Most of them are responsible. It’s the overprivileged that create problems. Whether it’s Boris Johnson or David Cameron, or others who were there before them, they already had it set up for their lives. School is one of the boxes they have to check. If it were not Eton, it would be Harrow. If you get rid of Harrow, it will be the next school. Even if they talk about change, nothing changes for the small guy.”

So how does one reconcile this great education with the harmful policies promoted by its alumni? There is no clear answer; and Okwonga doesn’t try to provide one. Instead, Okwonga presents a thoughtful, vulnerable, and conflicted portrait of a school that has shaped his identity. The turmoil for the author is which parts to embrace and which ones to discard. Overall, Okwonga adds valuable insight into the ongoing conversation about education, fairness, race, class, and success. One of Them is an excellent book and, on a timely topic. I highly recommend it for the entire family.