It is not an understatement to say that Ngugi Wa Thiong’o is one of the most respected scholars in the world. His body of work continues to shape discourses about the role of literature in promoting culture, good governance, and human rights. In many ways, Ngugi’s position in literature is a testament to his radical vision that African creative expressions should be written in African languages. His texts are at once individual stories, and yet also they present universal lessons about love, betrayal, and failure. Within these human stories, we see the role of the state and how it can negatively impact society. For Ngugi, culture and literature go hand in hand. As exemplified by his novel, Weep Not, Child, in which Ngugi paints a devastating portrait of a family crumbling under the weight of colonial intrusion. In all of his texts, Ngugi’s writings are incisive and timely. They spotlight fissures in Kenyan society triggered by contestation over land and heritage; revolution and passivity.

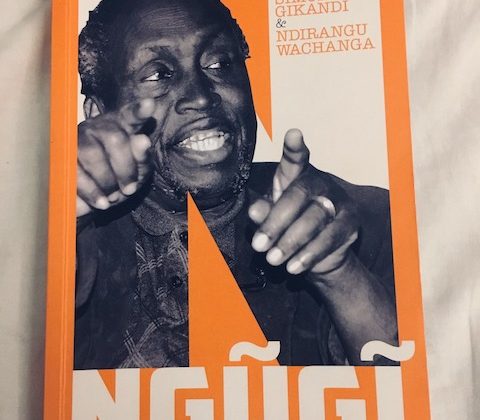

In a fitting tribute, a new book has come along to discuss Ngugi’s contribution to African literature and society writ large. Ngugi: Reflections on His Life of Writing, is edited by Simon Gikandi and Ndirangu Wachanga. The book gives a behind the scenes account on aspects of Ngugi’s life unfamiliar to the general public. In this book, Gikandi points out that Ngugi “is both rooted in a very specific Gīkūyū and Kenyan realm from which he has spread his wings to the world.” Ngugi’s global influence is presented through anecdotes and stories from his friends. Three broad areas stand out in this book: Ngugi’s earliest engagement with writing, his advocacy for preserving linguistic memory, and the impact of exile on his work. The book contains poems, essays, interviews, speeches and anecdotes from many friends.

In the first section of the book, Gikandi and Wachanga outline the impact Ngugi has had on the global literary landscape. Ngugi’s friends, old colleagues, and former students draw a portrait of a man gifted with an extraordinary talent and yet grounded by a strong work ethic. Publisher Henry Chakava calls Ngugi a “prolific and versatile writer of novels, dramas, essays, short stories, literary criticism, children’s books, orature, and translation.” In other words his reach is wide. Margaretta Wa Gacheru, a former student of Ngugi, notes he was “down to earth, dressed humbly, [and] never academically arrogant.” Similarly, writers, Peter Kimani, and Peter Nazareth both point out Ngugi’s love for conversation and his commitment to mentoring new writers. These descriptions highlight Ngugi’s accessibility and his advocacy for self-expression. For them, Ngugi promoted a participatory approach to the arts and was interested in engaging and broadening the literary landscape where books could be read at any level of society. His love for literature took him beyond Kenya to places like Makerere College, where Ngugi established himself as a writer. As Susan Kiguli points out, Makerere College, allowed Ngugi to make “the theme of memory and history central to his novels.” He publishes his first play, The Black Hermit, followed by his novel Weep Not, Child while in Uganda. The distance from Kenya also permits Ngugi the freedom to write candidly about life under colonialism. For him, the colonial state disfigured cultural identity, language, and the family life.

Second, the testimonials from colleagues help us to see the scope of Ngugi’s artistic vision. We get first-hand accounts of how Ngugi encouraged language education, particularly the effort that went into publishing books written in indigenous languages. Readers will find James Currey and Henry Chakava’s essays quite fascinating. The two publishers offer great insight into Ngugi’s role in decolonizing the English curriculum at the University of Nairobi. Currey notes that Ngugi wanted the curriculum to reflect a pan-Africanist approach; first, Universities would teach African texts, followed by diaspora texts, and eventually engage European books. This approach would create a new framework in which students learned from books that presented their experiences. For the implementation of this idea, Weep Not, Child—was adopted as a text to be taught in African Universities. Chakava’s essay is also gripping; it discusses the technical, financial, and political hurdles that confronted African publishers. Some of the barriers Chakava points out include the difficulty of finding language experts to help edit the texts. Also, it was expensive to hire artists and print high-quality manuscripts. Lastly, the two men had to endure harassment from the state—which saw their initiatives as political provocation.

Other writers like Kimani Njoge discuss Ngugi’s work on the first peer-reviewed Gīkūyū Journal at Yale University. Njoge notes that Ngugi was committed to preserving Gīkūyū memory regardless of the Journal’s popularity or reach. He felt that the “African continent continues to suffer the consequences of linguistic conquest.” In many societies English has created hierarchies that reward those who speak it. Thus we see a line of division between the educated and uneducated; the powerful and the powerless that is maintained through various institutions—schools, businesses, and government. Ngugi strongly felt that African writers should embrace African languages as a means of creating access and posterity for their communities.

Lastly, what makes this book a standout are the essays on exile. Both informative and candid—Odhiambo Levin Opiyo’s piece looks at declassified communications between Kenyan president Daniel Arap Moi and the British Secretary of State. Moi felt that Ngugi’s writings were promoting propaganda that threaten to Kenyan stability. He requested for the UK to deny Ngugi asylum and send him back. We also read about friends who offer Ngugi refuge. Rhonda Cobham-Sander and Reinhard Sander’s essay is enlightening because it sums up the cost of speaking out against the state. The two scholars detail Ngugi ‘s life in exile, particularly the lonesomeness he felt living in London and Germany. Cobham-Sanders notes that exile took Ngugi away from his children, his profession, and his income. For Ngugi, exile solidified his views that African thought should be preserved in African languages because he quickly saw the loss of language in his daily interactions.

All in all, Simon Gikanda and Ndirangu Wachanga should be applauded for this book. It is a useful companion to any Ngugi reading. It is also perfect for any person interested in African literature, history, or linguistic studies. It helps the reader to understand the role Ngugi Wa Thiong’o has played in linking African literature to society. It captures the depth and breadth of his work; which has been foundational in articulating human rights struggles across Africa. In these accounts, we see how Ngugi used his talents to shine the limelight on themes of poverty, cultural loss, political betrayal, and disillusionment. South African Professor, Grant Farred sums up Ngugi’s contributions perfectly: he calls his books “texts of consciousness.” These are writings that give voice to people who have been dispossessed of their resources and dreams.

Lydia Kakwera Levy